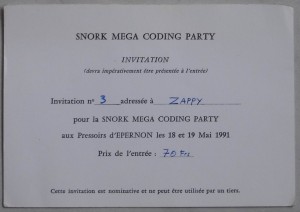

The Rising Force episode is one of my fondest coding-related memories. It happened at a coding-party, the Crystal Summer Convention II (CSC2). The Rising Force name obviously comes from Yngwie Malmsteen’s band. Let’s just say that at the time, we were fans. And it seemed to fit us like a glove. (For the record, I learnt for the first time about Malmsteen in a computer magazine, Micro News.)

Weary of war against competing groups, we had released Choice Of Gods without further ado. Without special announcement, without advertising, not even in the context of a coding-party – we simply sent it to a few swappers and called it a day. We were isolated from the small world of the demo scene, not aware of its gossip, rumors and stories. For the most part we stayed in our little corner. The Rising Force case was different. For the first time we went to a coding-party with a new creation, with the explicit goal of winning the demo-competition that took place there. We were going to witness people’s reactions live, on the spot, in realtime…

When we got there, we already had the screens. There wasn’t much left to code, we basically just had to put everything together, stitch one screen to the next, transfer that to a disk, done. And we naively thought we would wrap it in a few hours. That was a fatal mistake! Maybe a bit illogically it is, I think, notoriously difficult to code efficiently during a coding-party… Except we did not know that yet. It is impossible to code in a coding-party because too many extraordinary things happen all around. Too many people to meet, too much to say, too much to see. How can you focus on a task when speakers and decibels explode around you? When dozens of people constantly interrupt you for a chat? How do you track and kill a particularly nasty bug, which requires discipline and calm, in the midst of chaos? You guessed it, what had to happen did in fact happen: throughout this party I faced a bug… wait, no, not just “a” bug, it was the mother of all bugs. That was Murphy’s Law at its best: the bug that never happens, except when it can be the most damaging. Before we arrived, the organizers had already collected all competing demos, and thus they more or less already knew who would ultimately reach the podium. Oxygen, an already famous ST group, had joined the party with a finished demo, worthy of them. And then there was Nucleus/HMD as a challenger, with a demo called Phototro. Fighting like hell to finish it on time, his goal was to beat Oxygene at their own game for once.

And then, there was us. We arrived there after everyone else, but we did arrive anyway. And the small and little-known group named Holocaust was about to become a huge, a giant grain of sand in the well-oiled Oxygene machinery.

To be fair we only had a few scraps of demo, small pieces that we tried to pick up and put together. Design was lacking. It did not look polished or anything. Nonetheless, it was more than enough. Because of our isolation, because we had stayed away from “the scene”, we had never fully realized how good or how bad we were, compared to the competition. And thus what happened when one of the CSC2-people checked out our stuff was a genuine surprise to us.

Unforgettable: here we are, Elric and myself, showing a few screens to one of the jury members. The man in front of us, initially imperturbable, does not pay much attention. And then you see a spark of interest. And then something like a shock. His smile melts away. I think he realizes that the two scruffy mutants in front of him may be more than just Sunday coders after all. One of our specialties appears on the screen: a twisted mix of precomputed delta-compressed vectors, spectacular FlexiScroller, real-time 3D, all of this running at 60 Hz with, icing on the cake for us, a tiny touch of design to seal the deal. The man in front of us is stunned. He stammers out a few words, and without further ado he walks away, starts to rush behind the scenes, disappears. I suppose he went to tell the other guys that there might be a slight change of plans…

Elric and I are stunned as well. Receiving messages on the Minitel praising Choice of Gods is one thing. But this right here is something else entirely. It is much more striking, much more convincing: it is real, it is live. At that moment I started to realize, gradually, that we had gone beyond what I had imagined. It felt like not only we had reached the same level as our models and heroes, but in fact we had gone even further. And maybe we were in turn playing the role of pioneers, adventurers discovering new horizons and new possibilities.

While Elric follows the man behind the scenes to show off the rest of the demo (I am told this was epic!) I focus on the tedious bug that has kept me busy for several hours now. I try everything I can. I check everything. I recompile 100 times. I rant. I swear and I sweat. The organizers, friendly enough, push back the deadline for us, hour after hour. In vain. Meanwhile, I am in hell. As said before, I do not like doing things halfway. I am passionate. I put everything I can, all my heart and all my soul in what I do. And bloody hell that day, I thought I’d go mad. Mad with rage against this stupid machine that crashed constantly. I wanted to scream, to hit something, to throw the keyboard against a wall. Nothing worked, nothing. It was incomprehensible. A minor innocent change could make everything crash for no apparent reason. Or rather, there was a “reason” in a way: Murphy. Since we had an opportunity to beat Oxygene, HMD and all the others, there had to be something blocking our way, right? That is the Law. So time passed. And passed. And then so did the deadline. Disgusted, enraged, I had tears in my eyes: that kind of bug had never happened before! Never like this! It only happened, of course, when the stakes were high.

The competition took place in a small room, one floor down. People were starting to move, going there first to grab good seats. My eyes had not left the keyboard a single moment since the day before. And they still could not. I could not give up. Never! Not as long as I breath! I persisted. Minutes went by. The last remaining people left the room. The contest was about to start. Bitter, without much faith in it, I tried a final change… Will anybody ever believe it? It was there, and it was obvious. It was right there in the middle of the unpacking routine, which we did not write ourselves and which I would never have suspected. There it stood, proud and stupid, the most destructive bug I have ever faced. I compiled in haste, cold sweats going down the spine, and I ran the demo.

It worked. It was unreal. All the changes made since the previous day, all the pieces of the puzzle fell into place. The demo was running. I could not believe it. It was insane. It was the worst scenario I could have imagined, the meanest joke ever: everything worked, just a tiny bit too late. It was fucking unbelievable.

Too late? I was pumped full of adrenaline. I was over-excited. Disgusted as I have never been, vengeful, willing to try anything to tame this… this… this fucking bullshit piece of a demo! A second of eternity. And action! I never acted so fast in my life. Fingers fly over the keyboard. Floppy disks are inserted in the drive at the speed of light. I compile. Painfully slowly the demo is transferred to disk, one sector after the other. I have my finger on the drive’s eject button. I am already up, ready to sprint as soon as the drive’s LED goes off. Now! I run like hell, my mind is stewed, I rush down the stairs like a madman, raising the disk high in front of me… When I finally manage to find one of the guys in charge of the contest, and articulate some intelligible words to explain what the hell is going on, there are only three demos left to show on the big screen. But I won! I did it! It’s over! I got rid of that damn disk! I can now collapse, sleep, forget, relax…

I find Elric, staring blankly ahead. I am so tired. I explain the situation to him, and I finally take a look at the big screen. As a matter of fact the last two official demos to be projected there are the ones from Oxygene and HMD. Renewed interest. I check them out, as a connoisseur. They are rather good, but they lack something, they are no masterpieces. The Oxygene demo ends. I hold my breath.

One of the speakers starts to talk. Yes, there is a demo left to show. Yes, this is the one from Holocaust. Yes, it should have won if it had been completed in time. But it was not. And there are some minor bugs left in it, so…

True enough, it still has a few weird rendering bugs. Sorry, had no time to fix those. At least there is something to see. The demo is shown on the big screen, and I discover it at the same time as everyone else. I did not even have time to test if that disk worked from start to finish! But everything runs well. No crashes. I hear some reassuring comments around me: “Is this running on STE or STF?”. That one made me smile: dude, of course this is on STF! If you think we need an STE to do that, you’re dead wrong! Fullscreens, 3D, fractal mountains and a few effects never-seen before on ST catch a spell on the audience. Nobody expected anything like that from this rather unknown group… The demo ends… and we get a standing ovation! I will never forget that bit. After days of fighting that bug, this was a wonderful, extraordinary reward. I’m smiling, I’m on a cloud. Was I tired a minute ago? My fatigue is completely gone. This was the moment we understood that we had done it. We had reached our goal. We could beat our former heroes, Oxygene and others, at their own game. We could start believing in ourselves.

There are some days in life that you never forget. I had just experienced one of them.